I updated this blog for the first time in nearly three months last week, but I couldn’t update again without discussing the tale of my recent experience of dealing with a very difficult company at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. This encounter was very unpleasant, stressful and infuriating. Despite my anger, I’ve decided not to name the company involved, but for the purposes of this blog I will refer to them as Sunshine Inc.

This was my fourth year of reviewing during the Fringe and my first experience of being a Fringe editor, as I took up the post of Scotland Editor at The Public Reviews in May. In the midst of sorting through the thousands of Edinburgh Fringe PRs I received, my editor, John, forwarded me a PR for a Fringe show, suggesting that we book tickets and make a fun evening of it. The show was being performed by Sunshine Inc, and was presented as a two-hour long interactive comedy show, that involved actors impersonating characters from a famous TV comedy.

I booked the tickets for the show through their internal PR contact, a woman I’ll call Melina, who, I have to stress was very polite, helpful and friendly at the beginning. I did have to move the tickets by one day because of a scheduling clash, but again, Melina was very accommodating, and both myself and John were very much looking forward to the evening.

The show, however, was not like we expected, and we quickly realised that while the characters in the piece were designed to look and sound like the TV characters – they dressed similarly, and they even used their famous one-liners – this was where the similarities to the TV show ended. The evening consisted of these actors using new and ‘original’ content instead of established sketches from the TV programme, which wasn’t what I was expecting. Suffice to say, I didn’t enjoy Sunshine Inc’s offering, and I wrote what was I felt was a negative, yet honest and fair review, which was published on The Public Reviews website shortly after. In my review, I stated that the show was “unauthorised” as when I researched the show, I found a number of articles and quotes from the makers of the TV show saying that the show had not been authorised by them. Quotes from Sunshine Inc’s Managing Director, Francis, revealed that he hadn’t contacted the makers of TV programme to ask for permission to use the characters. Furthermore, on Sunshine Inc’s website they stated in the small print that their work had no association with the makers of the original TV show. So, with this information to hand, I mentioned in the review that the show was unauthorised.

A few days after the review was published, Melina emailed me to ask if we had any feedback on the show, and I replied with a link to the review, along with a brief response explaining that I hadn’t enjoyed the evening, but thanking her for inviting me and John along.

Melina’s response was interesting, to say the least; she emailed me back almost immediately and asked for the details of our “Managing Director” stating that there were points in my review that were of “great concern”. I responded, explaining that John, my editor, was the best person to contact and included his email address.

However, Melina emailed me again to ask for John’s mobile number, but because John was reviewing throughout the day, I was unwilling to share his phone number without his consent, or without him knowing what was going on. I decided not to respond to her email immediately, and concentrated on getting in touch with John to explain the situation.

As I tried to get hold of John, however, Melina continued emailing me demanding John’s phone number, saying that Sunshine Inc’s managing director, Francis, wanted to speak to him. Again I didn’t reply to her emails as I was concentrating on getting in touch with John. However, Milena’s emails continued, and she then began demanding that I remove the review from the website “immediately”. She also claimed that the show was authorised, yet didn’t say by who, and didn’t produce any evidence of this authorisation. When that failed to elicit a response from me, she further claimed that my review was “lies” and was therefore “libel” and again demanded I take the review down “immediately”, or they “would take legal action'”.

After reading these emails, John asked Milena to send him an email detailing her concerns, and to also highlight what parts of the review that she and Francis believed to be libellous. He further asked her to include the evidence of their authorisation so that we could address their concerns. Milena, however, ignored this, and emailed me again, telling me to take down the review before they took legal action. I replied, repeating what John had said, and also stressing that we couldn’t help them until they told us what issues they had with my review. I also asked her to send me evidence of authorisation, and asked for specifics, including the details of who exactly had authorised the show, such as the TV channel, the production company or the show’s writers.

Milena responded, ignoring my request, offering no evidence of authorisation, and further accusing me of trying to discredit the company, alleging that I had something against Sunshine Inc. This is untrue; I had never heard of Sunshine Inc until John forwarded me their Fringe PR in May. After reading this email, and following legal advice, I was told not to respond to any further emails from either Milena, Francis or any other representative of Sunshine Inc, as they had stated they were taking legal action, and could use our emails against us in the future. The lawyer also assured us that if they really were taking legal action, we’d be hearing from their lawyer, and not them, as they would also be told not to contact us for the same reasons.

However, despite my silence, Milena continued to email me throughout the day, and her emails became steadily more aggressive and more bizarre. John even forwarded me an email that Milena had sent to him, alleging that I was involved with a rival theatre company, naming the founder of that company, a woman I shall call Julie, and stating that this company had a “history of malicious intent” against Sunshine Inc. Incidentally, when Milena emailed John with this allegation, she inadvertently libelled me and Julie by alleging we were working together. These emails culminated in Milena taking a screenshot of my Twitter account, stating that the nature of my tweets regarding their show, which had been written after the review had been published, showed my negative review had been “premeditated” and that they were “taking further action”. They further accused me of “gross unprofessionalism”.

I contacted the Fringe Media Office to ask for advice about the situation. To my surprise, they told me that they were aware of what was happening, as Sunshine Inc had contacted them earlier that day. They told me that in a phone call that lasted around an hour, both Milena and Francis had spoken to Fringe media officers, demanding that the Fringe use their “considerable power” to force John and me to remove the review from The Public Reviews. The Fringe Media Office refused, as they don’t possess that power, nor do they want to.

A few days later, someone from Sunshine Inc called my mobile, but I let the call go straight to answer phone. They didn’t leave a message, and luckily, they haven’t tried to phone me since. Their emails, however, continued until the end of the Fringe, as they emailed John on several occasions to ask for the details of our “Managing Director” and for an address, so they could send an “official letter of complaint.” Eventually, John emailed them back, explaining that we had no managing director, we had no official address as we are online media, and that the best way to get in touch was to email him with specific concerns. Which, irritatingly enough, was what we asked them to do weeks earlier, when they had first made legal threats. They responded, asking “Who owns and runs The Public Reviews?” To which John explained that he did, and we haven’t heard from them since.

This happened during the second week of the Fringe, and while I like to consider myself as an experienced and confident reviewer, this incident shook me to the core. It made me question myself, my writing, my abilities and my voice, and was an extra stress during an already incredibly stressful time. I trained in art journalism for two years at university, and I have worked hard for the last three years since graduating to establish myself as an honest, objective and constructive critic. While I have had my fair share of abuse because of my reviews, this is the first time that I have been threatened with legal action for what I have written. I researched the piece thoroughly, as I do with every review I write, and I wrote a truthful and accurate review.

What’s very interesting, however, is that Sunshine Inc had one other reviewer attend the show, who also gave them a negative review. I have spoken to the editor of that publication, and they have not been contacted by anyone from Sunshine Inc. Recently, I made contact with one of the writers of the TV show, who confirmed that Sunshine Inc had never received authorisation from him to use his characters in their show.

Reviews are, essentially, the reviewer’s opinion, and as with any thing else in life, opinions will differ on almost many subjects, especially when it comes to performance. People are entitled to disagree with critical opinion, just as they are entitled to disagree with popular opinion. However, threats of legal action, and the intimidation, bullying and harassment of journalists simply because someone disagrees with what they have written, are immoral, unethical and odious. I cannot and will not be treated this way, by a company that are so desperate to undermine my authority and my review that they are prepared to not only accuse me of libel, but also in turn, libel both me and Julie in email correspondence. I have no idea if Milena and Francis have threatened journalists before, but judging by how quickly they threatened me with legal action, I would hazard a guess that this probably isn’t the first time that they’ve done this.

My advice to any company that is disappointed with a review is to see what they can take from it. If the review is constructive, then there will be something positive in there that you can learn from. If the reviewer has made an error, such as a spelling error, or got the name of an actor wrong, then feel free to contact them and tell them. Journalists, like all human beings, are fallible, and often work to very tight deadlines, especially during Fringe time. Tight deadlines, full schedules and many, many sleepless nights can lead to mistakes in copy. Editors are often very happy to correct inaccuracies when contacted.

However, a difference in opinion is simply a difference in opinion. Libel law exists to protect people who have been libelled and who have had very unfair things said about them in print. It does not exist to prosecute journalists who give a show a negative review, and it most certainly was not created to be used as a threat designed to intimidate journalists, editors and bloggers. Libel is a very, very damaging word and process, it comes with responsibility and should only be used if there is an actual case for libel proceedings. Journalists are busy people. Journalists are especially busy during the Fringe; we don’t even have the time to respond to the most basic emails during August, let alone waste precious hours and even days, dealing with baseless and utterly false allegations against us. I am very angry that I had to devote what little time I had during the Fringe to Sunshine Inc, because it cut into my reviewing schedule, which meant that I couldn’t attend the shows that I really, really wanted to review.

So to all journalists and bloggers: familiarise yourself with UK media law; study it until you can recite it. Join the NUJ – they have lots of lawyers who can deal with threats like this on your behalf. Stand your ground, don’t give into intimidation, bullying and aggressive, underhand tactics by “companies” like Sunshine Inc.

To all the people who supported me during this difficult time, including John and Glen at The Public Reviews, my close friends and family, the Fringe Media Office, Liam Rudden of The Edinburgh Evening News, Nick Awde of The Stage, and the CATS panel, including Michael Cox, Joyce McMillan, Mary Brennan, Allan Radcliffe, Mark Brown, Neil Cooper, Mark Fisher, Thom Dibdin and Gareth K. Vile: thank you. Your words and advice were of great comfort, and I’m so glad that you took the time to listen to me and support me last month.

And finally, to Sunshine Inc, I will say this: journalists communicate with one another. This means that if you threaten a writer or a publication with legal proceedings, other writers will hear about it. Once others learn about your treatment of journalists, it damages your reputation more than any negative review ever could. Some might say that’s ironic, but to me, that’s poetic justice.

Update: Following a request from Interactive Theatre International (formerly Interactive Theatre Australia) I am happy to confirm that the show and company in this blog have no connection with Interactive Theatre International or their show, Faulty Towers The Dining Experience which was performed at B’est Restaurant at this year’s Fringe.

Tags: CATS, comedy, Critics Awards for Theatre in Scotland, edfringe, Edinburgh, Edinburgh Fringe Media Office, fringe, Journalism, libel, mclibel, media law, National Union of Journalists, NUJ, PR, Review, reviewing, reviews, The Journal, The Public Reviews, theatre

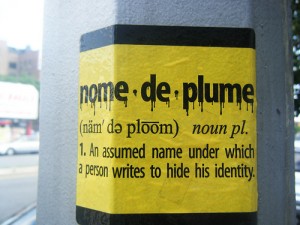

In the age of new media, how do we value anonymity? Does using a pen name devalue journalism? The recent publication of a review written by a critic using a pen name ignited a debate between critics and performers on the need for pseudonyms in criticism. Some said that anonymous reviews “…completely negate the credibility of your magazine”, whilst others dismissed the practice as “cowardly”.

In the age of new media, how do we value anonymity? Does using a pen name devalue journalism? The recent publication of a review written by a critic using a pen name ignited a debate between critics and performers on the need for pseudonyms in criticism. Some said that anonymous reviews “…completely negate the credibility of your magazine”, whilst others dismissed the practice as “cowardly”.